Oral healthcare report

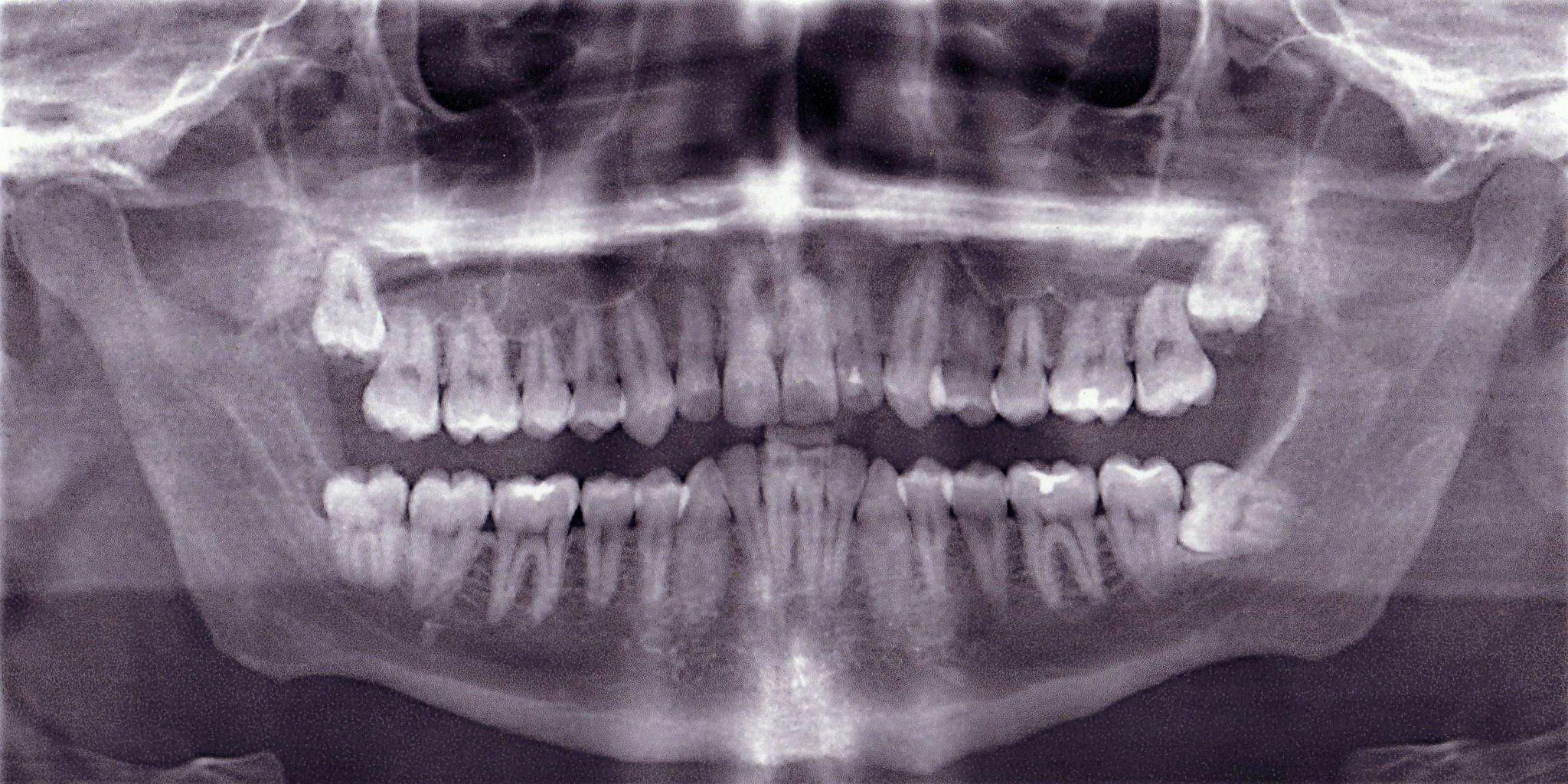

▲ Photo by Eric Dykstra on Flickr

This is an executive summary of our investigation into oral health

Oral diseases (such as cavities) affect around 3.5 billion people worldwide; around 45% of the world’s population (WHO, 2022). In turn, it is likely that the severity of dental conditions (in terms of the suffering they cause) is underestimated—at least for people living in regions with poor access to dental healthcare. While oral healthcare is not necessarily under-resourced on a global level (e.g. countries such as the UK and US invest large amounts of money into both preventative and curative oral healthcare), some regions are extremely under-resourced, with little or no access to dental treatment. However, interventions such as fluoridation are an extremely cost-effective way to reduce oral health problems.

Why is oral healthcare a promising area for improving global wellbeing?

Oral diseases (such as cavities) affect a vast amount of people worldwide; around 45% of the world’s population. In areas such as the UK and US, these disorders are relatively well-managed; we have fluoride in our toothpaste and sometimes our water, and easy access to a dentist. But oral healthcare in many low and middle-income countries (LMIC) is extremely limited.

For example, data from the WHO indicates that there are only 3 dentists in Chad—yet there are 12,751 in Belgium (a country with a smaller population size). This is not a one-off: there is a general pattern whereby oral healthcare in lower-income countries is often very under-resourced.

This is a problem, because poor oral health significantly impacts upon wellbeing. First (and most significantly), oral health problems can be extremely painful when left untreated; a small cavity is not necessarily painful, but a dental abscess is. Increasing access to dental care in LMIC would reduce the suffering that is caused by chronic dental problems. Second, there is some evidence that poor oral health independently increases the risk of other conditions such as coronary heart disease and diabetes: while this remains unproven, if so this would further increase the beneficial impact of improving oral health. Finally, there is evidence that poor oral health lowers attendance at school and work.

In turn, it is likely that these problems will become more significant in the future as lower-income countries undergo the ‘nutrition transition’; a switch towards more sugary foods. Evidence from ‘key players’ in the global sugar industry (such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo) suggests that they are already switching their focus towards LMIC.

Consequently, improving oral health in LMIC has the potential to be hugely impactful for improving global wellbeing. Yet this area has been somewhat neglected, because oral healthcare is often poorly linked to existing healthcare systems. In addition, many health organisations are especially focused upon the diseases which impact upon mortality: while oral health has significant impacts upon wellbeing, it is not a key driver of mortality in the way that some other health conditions are. This presents a missed opportunity, as there are a number of oral health interventions that have been shown to be both impactful and cost-effective.

With this in mind, we argue that improving oral health in LMIC is an important area for effective philanthropists. In particular, preventative measures such as fluoridation (milk and salt be fluoridated, in regions with low piped water coverage) are likely to be extremely cost-effective. Further interventions, such as training local dentists, may also be an impactful method towards solving this neglected problem.