Guide to the changing landscape of climate philanthropy

▲ Photo by Daniela Cuevas on Unsplash

This is a summary of our investigation into the climate philanthropy landscape through 2021

This report was authored by Johannes Ackva, Luisa Sandkühler, and Violet Buxton-Walsh.

This and our ongoing climate research continue to inform the work of our Climate Change Fund.

Climate action and philanthropy have changed rather dramatically over the last year.

2021 has seen an unprecedented effort to include climate spending in an ambitious infrastructure package in the United States, accompanied by a ~50% increase in private cleantech investment. Internationally, apart from traditional climate leaders such as the EU and the UK, other countries have raised their ambition, with China’s (late 2020) commitment to reach net-zero in 2060, and India’s commitment to achieve the same goal in 2070.

Climate philanthropy by foundations was at roughly $2b last year and is poised to increase significantly, probably almost doubling this year, with large new pledges (such as Bezos’ Earth Fund) coming into effect. Traditionally, individual giving has dominated climate philanthropy, putting the total closer to $5-$10 billion last year, with a significant increase expected for this year as well.

This guide is about what we believe the implications of this changing landscape to be for donors that are motivated by maximizing positive climate impact. It’s intentionally a “guide,” not a research report, utterly oriented towards action-relevance but deeply informed by data and relevant scientific facts.

We structure this guide in three parts.

Part I provides a mapping of the climate action and philanthropy space, introducing key facts as well as key uncertainties that characterize the terrain and that, taken together, hopefully provide some clarity in a confusing and dynamic space.

Part II is about strategy. Given the landscape and how it has changed, what should we do?

Part III explains our grant-making through the Founders Pledge Climate Change Fund, articulating how we have implemented this strategy. However, our intent is much broader than explaining our own grant-making. Parts I and II do stand alone and hopefully provide useful observations and principles for other philanthropists who might come to different conclusions regarding specific grants.

Part I: Key facts and uncertainties

Key facts

Climate change is an incredibly complex challenge and the climate space is dynamically evolving. To see through the confusion and be able to act, it is important to identify the most important action-relevant facts: key characteristics of the challenge that determine what the most effective philanthropic actions are likely to be. We focus here on what we believe to be the three most important stylized facts about climate:

Climate philanthropy has surged

Climate philanthropy has been growing rapidly. While the climate space is vast and will eventually be able to absorb this influx of money well, this surge makes it likely that filling the average open funding margin is less impactful than it would have been a couple of years ago. This implies that funders have to be more strategic in order to find opportunities where funding makes a large counterfactual difference. This means that funders have to identify (i) where their money is truly additive (e.g. ensuring that they are not filling gaps that would have been filled anyway by a different funder) and (ii) where the activity being funded is truly additive (e.g. whether it is a useful addition to the space or whether they are simply funding the 1001st voice making the same argument in a particular policy debate).

Climate attention is not, by and large, where future emissions are

While the surge in climate action and philanthropy is certainly good news and there are spaces where additional funding adds little in terms of additional impact, there are still severely neglected spaces where we should expect lots of future emissions but where right now there is fairly little attention.

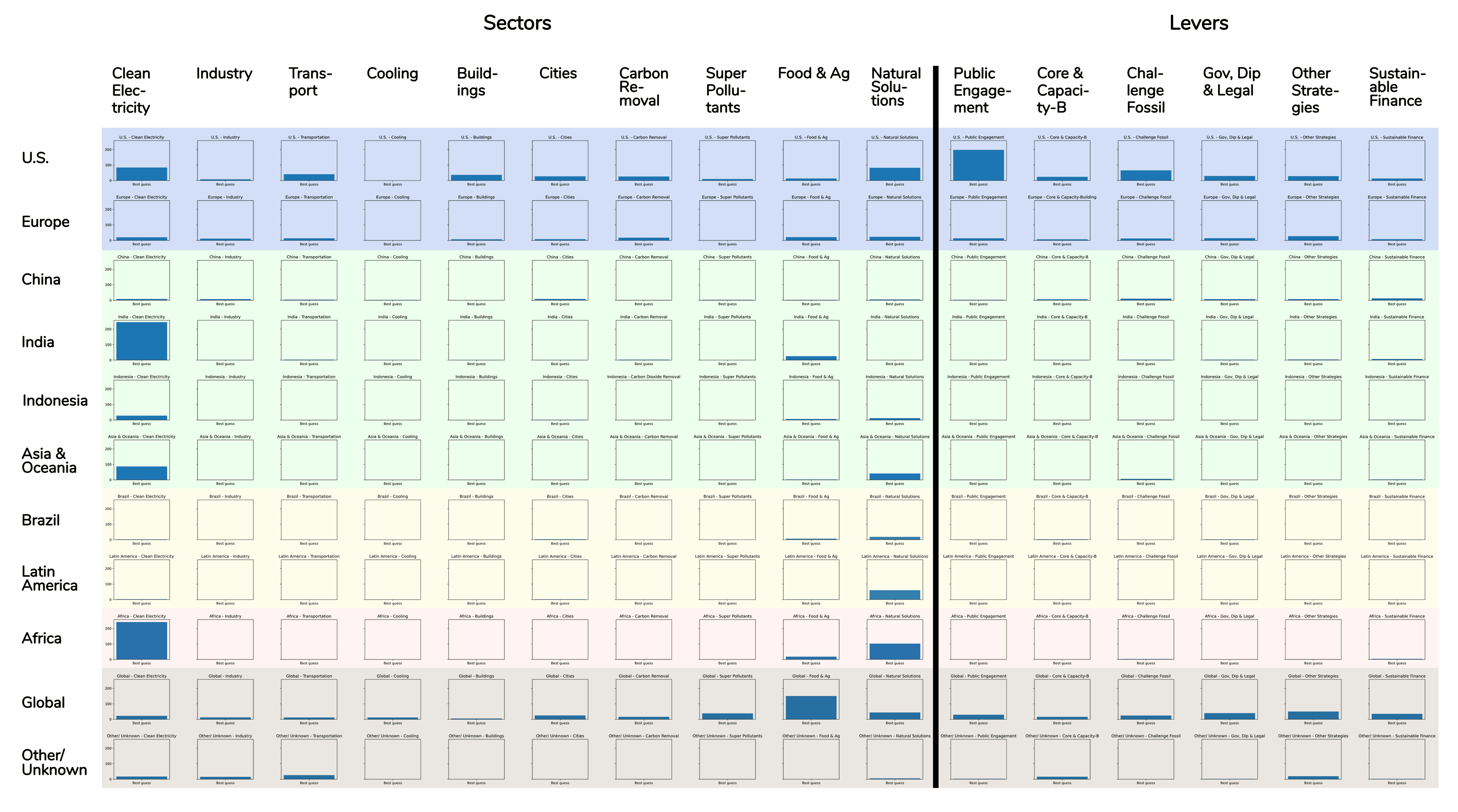

To understand what is currently neglected, we built on the foundational work of ClimateWorks (2021), including commitments up to 2020, but added in major new commitments from this year using their categorization scheme. We particularly focus on including the two largest commitments we are aware of from this year, Bezos Earth Fund, pledging 10bn for climate action this decade, as well as the Global Energy Alliance for People and the Planet (of which the Bezos Earth Fund is a member) pledging 2.5bn over 5 years for renewables in developing countries. As many of the grants are quite new with little public information, we include significant uncertainty bars in our full estimates.

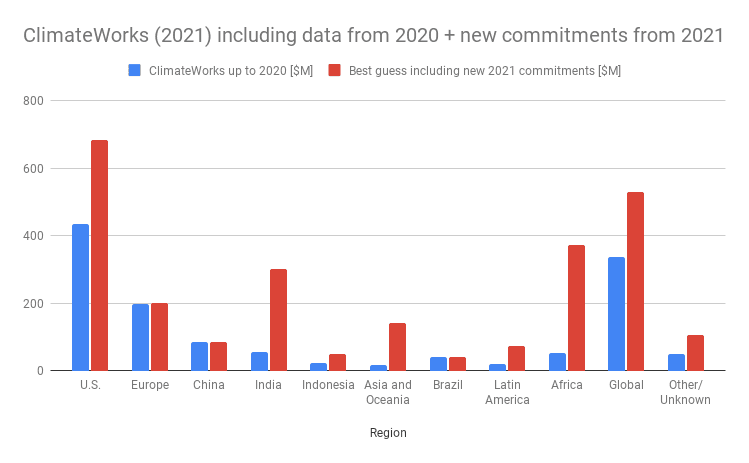

Figure 1 below shows very significant changes in annualized estimates of climate philanthropy through new major commitments in 2021 compared to 2020:

Figure 1: Distribution of climate philanthropy by sector, based on ClimateWorks (2021) and own analysis

Figure 2 provides the same by region though we are very uncertain about the distribution of funding of the Global Energy Alliance for People and the Planet amongst non-OECD economies, so we below focus on OECD/non-OECD comparisons:

Figure 2: Distribution of climate philanthropy by region, based on ClimateWorks (2021) and own analysis

Figure 3: Sector/region combinations, based on ClimateWorks (2021) and own analysis

We believe the following key findings from the data warrant special highlighting for climate philanthropy prioritization:

- Philanthropic funding skews heavily towards clean electricity. Philanthropists continue to pay little attention to hard-to-decarbonize sectors. While there is some uptick in philanthropic funding for those sectors such as industry and heavy-duty transport through Bezos Earth Fund commitments, these are dwarfed by other increases. Insofar as philanthropy sets the agenda for civil society and policy, this is worrisome as it continues the overemphasis on relatively mature and popular technologies rather than focusing on those parts of the economy that are not yet trending clean. These are the sectors that most direly need more attention.

- While there is a lot of philanthropic funding for clean electricity, this is almost entirely focused on renewables, with minimal contributions for other clean electricity sources such as nuclear power. While the ClimateWorks numbers do not distinguish between different clean electricity sources, it is clear that most of this funding is focused on renewables. Additions from the Bezos Earth Fund and Global Energy Alliance for People and the Planet are exclusively focused on renewables.

- Topics that get the most public attention get the most funding. Areas that have been at the forefront of public attention in 2020 and 2021 or that are generally popular have profited disproportionately from the funding surge. This is true for forestry and other natural climate solutions that have received a large share of existing commitments from the Bezos Earth Fund. It is also the case for groups focused on building attention for climate action and/or for addressing previously neglected environmental justice concerns that have been another major focus of initial Earth Fund grants. It is increasingly true for work on super pollutants such as methane, given recent surging policy attention to the issue.

- There is somewhat more attention to innovation and innovation advocacy than before, with some of the aforementioned grants particularly focused on innovation in hard-to-decarbonize sectors and commitments from Bezos Earth Fund to Breakthrough Energy and Breakthrough Energy Action. We take this into account in our grant-making and assume that innovation advocacy in the US is less neglected.

- Regions that represent a small portion of future emissions receive a disproportionately large share of philanthropic funding. About 35% of climate philanthropy is targeted at the US and about 10% at Europe, even though those regions represent at most 15% of future emissions. While this focus has been more severe in the past, ClimateWorks (2021) numbers suggest that 66% of geographically assignable climate philanthropy is focused on the US, Canada and the EU. Given that those numbers reflect foundation data and that individual donors dominating climate philanthropy are probably more focused on domestic initiatives than foundations, this is almost certainly an underestimate of the true differential in geographic distribution of funding.

The data therefore show that climate philanthropy is disproportionately directed at the US and EU, even though these regions are together responsible for at most 15% of 21st century emissions. Yet, this is not necessarily a misallocation given that those jurisdictions also command a much higher share of climate attention, societal resource mobilization, and innovation capacity than the rest of the world.

This means climate philanthropy in those regions should primarily be judged by the degree to which they improve the climate response in those jurisdictions to facilitate global decarbonization, as the indirect effects of climate action in the US and EU can easily be 10x larger than their domestic effects.1

The data also show that some sectors and technologies remain quite neglected (albeit less so than before). This is true for sectors such as industry and heavy-duty transport and solutions such as advanced nuclear, carbon removal beyond nature-based solutions, and carbon capture and storage. By and large, climate philanthropy bets on the success of renewables and nature-based solutions and pays less attention to less-popular alternatives.

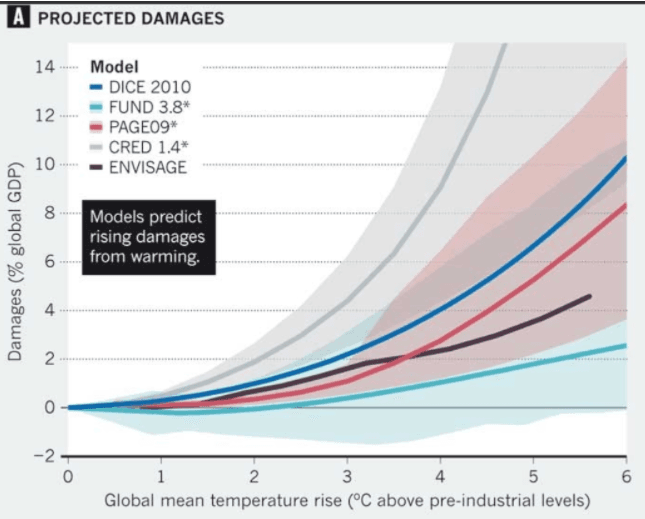

Climate damage is non-linear

The third crucial fact is that climate change gets increasingly unmanageable as it gets more extreme. While a world of 1.5 degrees would not be that different from today, a world of 3 degrees of warming would pose significantly more challenges, with risks being a lot more pronounced still at 6 degrees:

Figure 4: Some estimates on the non-linearity of climate damage (from Revesz et al. 2014)

While the displayed models have been heavily criticized for likely underestimating climate damage (and we agree), what matters here is not the level of climate damage, but the shape of it. On the median model of this set (page 9), climate damage increases about 5-fold from 1.5 to 3 degrees and about 8-fold from 3 to 6 degrees. Importantly, this basic pattern of increasing damage with increasing warming holds across all of those models and is consistent with many other approaches to estimating climate damage.

This leads to what might be a surprising conclusion – the goal of high-impact climate philanthropy is not to maximize emissions reductions but to minimize climate damage.

While this sounds technical, it has profound practical implications for high-impact climate prioritization: it is much more important to shift from 5 to 4.5 degrees if we are in a 5-degree scenario than it is to shift from 3 to 2.5 degrees in a 2-degree world.

Because we know that certain combinations of events are unlikely, this non-linearity also informs our actions in the face of uncertainty. For instance, it is unlikely that the world end up in a 5-degree world if all current mainstream solutions succeed. This suggests that philanthropists put more resources into solutions that could be vital if current mainstream solutions fail.

Key uncertainties

Every high-impact strategy to take action on climate, philanthropically or otherwise, carries significant uncertainty about outcomes (“How many emissions are avoided?”2) This makes it fundamental to think clearly about the role that uncertainties play in our decision-making. In this section, we make five important points about how to think about and deal with uncertainty:

- Avoiding uncertainty carries a heavy cost – certainly having little impact is much worse than probably having much larger impact.

- High uncertainty does not imply ignorance – even when we are quite uncertain, this is not equivalent to having no action-relevant information.

- Practicality is more important than precision when it comes to decision-making. What matters in guiding action on climate is not being precisely right about impact (e.g. an exact estimates of tons of CO2 averted per dollar spent), but rather being roughly right about relative impact (e.g. how different approaches to averting CO2 compare to each other) which is decisive for prioritization and taking action.

- Consider how different strategies are related. When strategies are characterized by many uncertainties, it is important to consider whether they are independent of each other or correlated, in which case scenarios need to be considered jointly.

- It is much worse to be too optimistic than to be too pessimistic given the non-linear nature of climate damage: it is very costly to be wrong.

This leads us to a principle we call robust diversification – when diversifying (i) we do so in such a way that uncertainties are negatively correlated and (ii) we pay special attention to robustness against the worst worlds – those where uncertainties could resolve in ways that lead to maximal climate damage. Additional effort in these scenarios is particularly valuable.

We apply this principle to four different uncertainties about (a) the degree to which we are already set on a low-carbon trajectory, (b) the adequacy of existing solutions and the related need for additional innovation, (c) the degree to which carbon lock-in prevents the diffusion of new technologies (i.e. limiting the potential of innovation), and (d) whether or not the current favorable geopolitical and climate attention situation will persist.

This leads us to favor strategies that assume that a lot of progress is still needed (such as (a) and (b) above): for instance, accelerating innovation, because being too pessimistic is better than being too optimistic. Per (c), it also leads us to complement innovation with efforts to avoid carbon-lock-in as the uncertainties about both strategies are negatively correlated: innovation is least effective when carbon lock-in is severe, and vice versa. We also prioritize solutions, per (d), that do not assume lots of international coordination and/or willingness to pay for climate action, given that it is quite plausible that the situation will deteriorate. This is where most climate risk is concentrated and therefore where additional mitigation is most valuable.

Part II: Strategy

We think of high-impact theories of change (strategies) as combining several impact multipliers, so after explaining what we see as the most important impact multipliers in climate we explain promising theories of change, each leveraging several of those multipliers.

Impact Multipliers

Given both the daunting nature of the challenge as well as the current surge of funding in the space, when seeking to maximize impact in the climate space, we believe it is fundamental to look for “impact multipliers”: reasons to expect that a given funding allocation will have an above-average impact by filling blind spots and leveraging effective mechanisms.

We think there are three primary sources of outsized impact in the current climate funding space.

Complementing rather than copying the behavior of other donors

This means focusing on approaches, technologies and regions that are neglected, under-served compared to their relative importance. Possible avenues include (a) supporting technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), carbon removal, and advanced nuclear that receive a small fraction of climate philanthropy and are often perceived negatively, (b) paying more attention to the hardest parts of the decarbonization challenge, such as industry and heavy-duty transport, and (c) expanding to regions where climate philanthropy, to date, is very low relative to future emissions, such as India, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Crucially, we must do this in ways that do not restrict energy access and thereby condemn these populations to poverty.

There are also three corollaries to neglectedness that have to do not with the substantive focus of funding, but rather with the kind of funding provided: from many interactions with donors and charities, we find that too much funding is risk-averse, impatient (focused on short-term wins) and focused on specific projects.

These phenomena suggest that many projects that are risky but worthwhile may not be funded, giving an impact multiplier to donors that are willing to be patient and risk-neutral. For similar reasons, we also think it is good to give unrestricted funding and to conceive of “overhead” not as negative, but as a positive organizational multiplier – an investment that allows a charity doing great work to invest in doing this work more efficiently and to attract more funding.

Utilizing key features of the climate space to maximize impact

One way to do this is to fund trajectory changes in situations that are pivotal because they set in motion dynamics that will self-reinforce.

Such feedback loops can be positive, as when virtuous cycles of increased investment enable cost reductions leading to further investments – a phenomenon observed with wind, solar and electric cars, where early investments were arguably trajectory-shaping. But they can also be negative, as in the case of carbon lock-in scenarios in which long-lived assets, infrastructure investments and the political economy they give rise to commit emissions streams decades into the future.

Philanthropists should also be sensitive to whether they are funding true policy additionality: they must make sure funded efforts do not simply make it easier to reach policy targets that would be reached anyway (in which case additionality would be zero: the money is wasted).

Funding the right type of work

We firmly believe that, on balance, funding advocacy and similar efforts to induce policy change and affect how societal resources are spent provides the most compelling proposition for impact-oriented philanthropists.

This is so for a number of reasons, such as the vast scale difference between philanthropy and public spending (leverage), the necessity of policy change and its ability to trigger private action (causal primacy), and the abstractness and intangibility of advocacy, which make it likely to be relatively underfunded.

Theories of change

Many theories of change make sense at face value: they are internally consistent and seem convincing. Thus, when prioritizing between different theories of change and interventions that could receive support, we need to prioritize based on observable and comparable characteristics to identify high-impact strategies. That is why, apart from examining theories of change in detail on a mechanism level, we primarily rely on exploiting systematic features of the climate space and the interventions to make relative judgments in an uncertain world.

In other words, we evaluate how different theories of change perform alongside the identified impact multipliers to give rise to expectations of particularly high impact.

We currently have identified four theories of change that we expect to be particularly promising, as summarized in Table 1:

Part III: Our grant-making

In line with this analysis of the situation and strategy, we have made the following grants late last year and this year.

Capitalizing on the Biden moment

We deployed $850,000 to the Clean Air Task Force (CATF) and $400,000 to Carbon180 directly after the Biden victory to enable those organizations to optimally engage with the incoming administration and utilize the momentum to push for innovation in neglected technologies, based on our analysis of the special opportunity for climate impact under a Democratic President in a political environment with unusual willingness to spend boldly in the wake of COVID-19.

Although a final analysis of impact of those grants and our predictions is not yet possible due to ongoing legislation, our intermediate understanding is that these grants have been quite successful.

Several of Carbon180’s policy suggestions have recently been taken up by US policymakers. C180 recommended that the Department of Energy launch an initiative to reduce the cost of carbon removal to $100 per ton and recommended that appropriations for carbon removal be significantly increased. Both ideas were implemented: the recently enacted infrastructure bill contains $3.5 billion in new funds for direct air capture (DAC) efforts.3 Similarly, the recently-passed infrastructure package reflects many of CATF’s priorities, such as increased support for carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen infrastructure, industrial decarbonization, and advanced nuclear demonstration, with a total of $30 billion for clean energy provisions championed by CATF. Because both Carbon180’s and CATF’s foci are overall fairly neglected on the political left and there are few fervent advocates for carbon removal, CCS, and advanced nuclear, it is plausible that these organizations had significant impact in the provisions of the infrastructure bill they worked on. We will provide a more detailed and rigorous retrospective grant analysis once the Build Back Better Plan has passed as well (in 2022).

Avoiding carbon lock-in in emerging economies

While we examined other grant opportunities in the wake of Biden’s win and the Democratic win in Georgia, it became our impression that this space was increasingly saturated and that additional money focused on short-term wins would not have large additional impact, and that organizations doing incredibly important work had sufficient resources to do so.

We also observed a strong uptick in US-centric philanthropy and a moderate uptick in innovation-focused philanthropy and advocacy (including Bill Gates’s How To Avoid A Climate Disaster and commitments from Bezos’s Earth Fund to innovation in hard-to-decarbonize sectors), which led us to broaden our scope and explore other theories of change, in particular around avoiding carbon lock-in in emerging economies.

This has led to a large organizational investment and globalization grant for CATF which is focused on allowing CATF to become a truly global organization, with new presences in China, India, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, as well as a strengthened presence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although CATF is a longtime grantee of ours, this grant evaluation was driven by a fundamentally different rationale than prior investigations and grants. Instead of focusing on innovation advocacy in OECD economies, this new grant will support trajectory changes and efforts to avoid carbon lock-in in those regions of the world where energy demand growth is concentrated.

We are also investigating further grants under this theory of change, focused on co-benefits of air pollution and climate advocacy in Southeast Asia and accelerating mature clean technologies, such as solar PV, through strengthening cleantech ecosystems in emerging economies. We currently believe that a fair amount of our future grantmaking will be concentrated in emerging economies, in particular if – as we expect – the US political opportunity somewhat dries up after the 2022 midterms.

Innovation advocacy in Europe & advanced nuclear

While we believe that the US climate policy debate has become significantly more innovation-oriented, this is far less true in Europe. This is why we are excited to scale a new organization, Future Cleantech Architects (FCA), to help positively shape German, European, and global debates on innovation priorities. Over the past year, after being approached as advisors, we have closely observed this organization's impressive initial successes4 and we are now ready to invest in its ambitious growth, supporting its organizational development as well as key programs in hard-to-decarbonize sectors requiring more innovation, namely zero-carbon fuels, industry, long-duration storage, and carbon removal technologies. We believe that if FCA is successful this could significantly improve the German and European climate policy response. This work is also clearly additive; this kind of organization is much rarer in Europe than in the United States.

We believe that TerraPraxis continues to do incredibly important work around shaping a conversation for advanced nuclear to address critical decarbonization challenges, such as the decarbonization of hard-to-decarbonize sectors and the conundrum of how to deal with lots of very new coal plants that are unlikely to be prematurely retired.

As a very small organization and with a relatively small pro-nuclear funding landscape, TerraPraxis has not been able so far to scale to its full potential. For this reason, we not only invested in Terra Praxis’s programmatic work, but also in its organizational capacity.

In the wake of COP26, we also made a time-sensitive grant to the EEIST project to help make a critical argument about how traditional cost-benefit analysis underestimates the innovation returns of seemingly extremely expensive policies (such as early deployment subsidies). This argument reached 4M people through a professional PR effort (more details at Grant #1 here.)

As we head into 2022, we will continue to deepen our research and grant-making, trying to find the best opportunities by analyzing the funding landscape, identifying and evaluating new theories of change and finding and funding opportunities we perceive as bottlenecks and blind spots of the current climate response.

Notes

-

If this sounds hyperbolic, consider that small to medium-sized jurisdictions such as Denmark, Germany and California have been able to drive decarbonization outcomes – via driving cost reductions and technology improvements in wind, solar, and electric cars – that went far beyond their domestic emissions. E.g. Gerarden (2017) estimated that “32% of the global solar adoption due to increased technical efficiency would not have occurred in the absence of German subsidies”, while the virtuous cycle set in motion by these policies will eventually save gigatons of emissions globally every year, while, at most, saving hundreds of millions of tons in Germany (see here for a more detailed version of this argument). ↩

-

Or removed, in the case of carbon removal. ↩

-

In 2015, C180 was among the first organizations to advocate for DAC to be eligible for 45Q, the federal tax credit for carbon sequestration, and has consistently worked to raise the value of DAC under that program. ↩

-

Such as conducting and publishing a cleantech R&D priorities survey through the World Economic Forum and the TEC committee of UN Climate Change, hosting a cleantech innovation call with three UN organizations and presenting key neglected R&D needs in two events at COP 26 in Glasgow as well as taking the only European perspective in the release of ITIF’s 2021 Energy Energy Innovation Index. ↩